Noir with a Female Gaze

What is it about 1940s crime noir that is so irresistible and enduring? My love affair with the genre started in my early teens, watching movies like The Big Sleep, The Blue Dahlia, and The Third Man. I found them compelling; the high stakes, the larger than life characters and murky worlds in black, white and shades of grey. Not to mention the back drop of the war and a world in upheaval.

I loved crime detective stories most of all, where a tough guy like Marlowe would take on the bad guys, win, and end up saving some sassy dame (such as those frequently played by Lauren Bacall and Veronica Lake)

1940s noir is a visual treat, particularly the glamour of the female movies stars, Barbara Stanwyck, Betty Davis, Hedy Lamarr, Joan Crawford, Lana Turner and many others. When on screen, these women would outshine every other character for me. Their witty, clipped and droll dialogue compounded their allure. I was hooked.

Or so I thought.

A toxic genre

I was too young to understand then that actually most of the female leads in noir had met the rigid approval of the Hays Office, and the Hollywood Production Code, and the genre itself is a great example of toxic masculinity in movies. The Code’s business was to keep Hollywood movies clean as a whistle – and that meant stories had to be moral, and no characters had more rules and regs in the morality department than the women. The 1940s were after all, very conformist.

Consequently, female protagonists fell into some very clear types, defined by their moral attitudes and choices; the good girl, the femme fatale, and the fallen woman.

1940s crime noir is actually so obsessed with female behavior, that any woman who defies its mandate to be worthy and wholesome has little chance of redemption. The implicit question in every noir movie featuring a female lead is… does she deserve that ultimate reward for women, a happy marriage? If not, her destinations are graveyard or jail.

Having watched countless 1940s movies, I’ve deduced a simple morality system at work:

- Bad girls – particularly femme fatales – get bumped off.

- Men who love bad girls pay the ultimate price. i.e. they get bumped off too. Or if they have the love of a good woman, she might be able to save him just in time but only if he pays a price and realizes the error of his ways.

- Good girls who stay good will be rewarded – and often saved – by the love of a good guy.

- If a basically good girl errs on the wrong side, they still can get a shot at marriage, (or staying married) but only if they see the light in time and learn the error of their ways.

- Fallen women – who aren’t necessarily evil, but definitely unrespectable, might not die but they don’t get the guy.

1940s noir taught both men and women that erring from the moral path inevitably leads to downfall. It’s the degree of the downfall and the lessons learnt that decide how much they will hurt.

Mildred Pierce – a noir heroine for women?

In 1945 Mildred Pierce came along to break the noir stereotypes by giving us a ‘real’ woman in the lead (up to a point, this was the 1940 after all – the only black character, Lottie, is a racist stereotype of cute subservience). Mildred is middle aged, has female friends, is an entrepreneur, and split from her husband. She’s the 1940s attempt at a modern woman, but she’s still firmly in the ‘good girl’ category. Mildred’s biggest problem is that she loves too much and can’t say no. As a result, Veda her daughter is a ruthless narcissist (as are all femme fatales), who manipulates her mother. It’s only by breaking free of Veda’s clutches Mildred ends up with the possibility of happiness with her husband again. Like so many fallen noir heroines, when Mildred tumbles, there’s a good man to pick her up because she does the right thing.

Another sad reflection so visible in all 1940s noir movies is the ageism, racism and homophobia of the times. Depictions of anyone with these ‘afflictions’ either don’t exist on screen, or are portrayed as offensive and negative stereotypes.

So any fan of 1940 noir today has to ask themselves, ‘Can I turn a blind eye to 1940s values to enjoy these films? How much can I ‘love’ this genre, while knowing it peddles a sexist, ageist and racist world which is totally geared around white male gaze?

#bookswithvintagestylenotvalues

Creating Elvira Slate

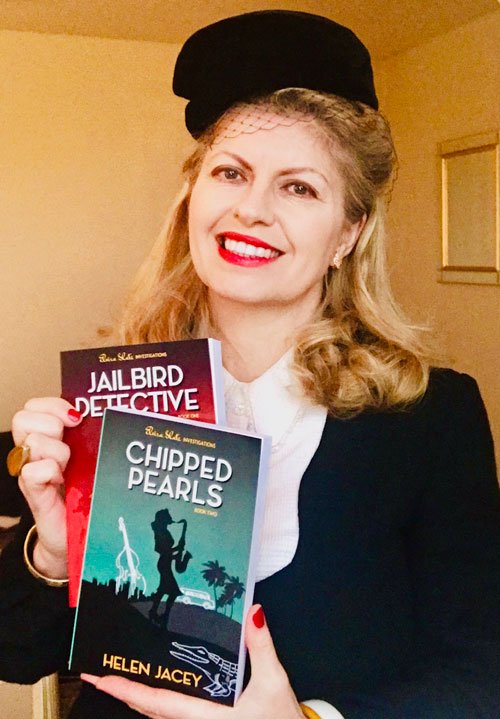

It was my jaded thoughts about the genre motivated me to create a form of 1940s crime noir as I wanted to see it. My book series Elvira Slate Investigations revises the 1940s by putting women and diverse characters at its heart, to really expose the conformity and oppressions of the era.

Having a female detective isn’t a straightforward case of subverting the genre, or flipping the stereotypes. A cynical, boozed up, loner male detective who talks tough and beats up bad guys can’t just come in female form.

Elvira Slate falls fouls of 1940s expectations of women, certainly protagonists. She is illegitimate; an ex-con, having served time in both Holloway Prison and Reform School; an abuse survivor; she is herself a fugitive from justice, a wanted woman.

There is an aspect of ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ to Elvira. Being young and attractive gives her to give her access to the 1940s sexist patriarchy that solely judges women on their youth and beauty. She can use her looks to play men who take advantage, or seriously underestimate her.

Elvira inhabits her world with a rare empathy for others’ suffering particularly if they are outcast or discriminated against. She is a champion of the underdog, even if some bite her when she least expects it.

Strong at the broken places

Elvira’s approach to life is very far from the tough guy mentality we see in so many 1940s male detectives, who can’t or don’t reveal emotion, even after a few beatings up and they are at their lowest. Philip Marlowe remains totally repressed, we actually know little about him.

Conversely Elvira wears her heart on her sleeve. Sometimes she doesn’t know what the hell she is doing, and isn’t afraid to admit it to herself. Her evolving mental health and working out the damage of her past is a big theme through the series.

Back in the day, a character like Elvira Slate would never be able to be a lead in 1940s noir. She would be relegated to a bit-part role of an undesirable or fallen woman – sad, hopeless with no chance of empowering herself.

Finally we get a chance to see an unfair world through one of these characters’ eyes.

Helen Jacey